Authors / metadata

DOI: 10.36205/trocar6.2025017

Abstract

Introduction: Adenomyosis increases the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. Recent clinical observations at 3rd Park Hospital Obstetrics and Gynaecology clinic have highlighted a significant number of cases involving women experiencing miscarriages and were found to have adenomyosis. The impact of adenomyosis on pregnancy outcomes is examined and management approaches that can minimize adverse outcomes are explored.

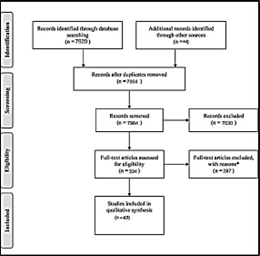

Materials and Methods: A review of relevant literature (2010-2024) from electronic databases using the PRISMA guidelines in selecting the relevant studies for review.

Results: Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) therapy can regulate maternal immunity. A low-dose aspirin can improve endometrial receptivity. Corticosteroids like prednisolone can correct immunological imbalances. Progesterone supplementation with dienogest can create an optimal uterine environment. Antioxidants like CoQ10 can reduce oxidative stress. GnRH-a administered for three months prior to conception can reduce adenomyotic lesions and improve implantation rates.

Conclusion: While no single treatment is universally effective, a comprehensive approach addressing the underlying pathways can minimize complications in pregnancies complicated by adenomyosis. Pregnancy in women with adenomyosis must be managed in a high-risk obstetric unit given its multifaceted role in pregnancy.

Recommendation: Administering GnRH-a for 3 months prior to pregnancy to improve placentation and reduce the risk of miscarriages is recommended.

Introduction

Adenomyosis, a condition characterized by the abnormal growth of endometrial tissue within the uterine myometrium, has become pertinent in reproductive medicine due to its potential impact on pregnancy outcomes. Recent clinical observations at the 3rd Park Gynaecology and Obstetrics clinic highlight significant cases of miscarriages and other poor pregnancy outcomes. All these have been associated with adenomyotic changes in the uterus, as revealed by in-house ultrasound examinations on the patients. These outcomes include miscarriages, foetal growth restriction, preterm labor, preeclampsia, atonic bleeding, uterine rupture, abnormal placentation, preterm premature rupture of membrane, and small for gestational age (SGA) infants (1–18). Managing pregnant women with adenomyosis is indeed a complex and multifaceted challenge, given the condition’s poorly understood pathophysiology, risk factors, and potential interventions. Currently, there is minimal research and literature on the appropriate approaches for managing adenomyosis in pregnancy. This review provides some insight into various approaches that can be explored to prevent adverse outcomes for pregnant women with adenomyosis.

Material and Methods

This review included literature (2010-2024) from electronic databases including PubMed, Cochrane Library, Google Scholar, and MEDLINE. The search utilized the PRISMA guidelines to select the relevant studies for review. The search yielded 7920 results, and 47 studies were finally selected for further evaluation and review. Studies that were outside the scope of adenomyosis in pregnancy, published in languages other than English, those with no access to full texts, those with unsuitable study methodologies and design, and those with insufficient data have been excluded (Figure1).

Pregnancy Complications with Adenomyosis

Adenomyosis adversely affects the uterine muscle layer and can manifest itself as focal and/or diffuse adenomyosis, and in rare cases, cystic adenomyoma (11,19). Khan et al. note that diffuse dispersion of numerous foci of endometrial glands and stroma within the myometrium is considered as diffuse adenomyosis (20). Circumscribed nodular aggregates on either anterior or posterior wall of the uterus are considered as focal adenomyosis (19). Harada et al. pointed out that diffuse adenomyosis involves alterations in the entire uterine muscle layer, particularly sub-endometrial constituents. This alteration is responsible for adverse obstetric complications (2). Cystic adenomyoma involves focal adenomyosis with further compensatory hypertrophy of the immediate myometrium (21). Diffuse adenomyosis alters the entire uterine muscle layer, particularly sub-endometrial constituents and increases the risks of pregnancy complications, compared to focal adenomyosis (2,11). Harada et al. and Tamura et al. established that women with diffuse adenomyosis will more likely experience preeclampsia and uterine infection (including severe conditions such as septic abortion and postpartum abscess formation) than those with focal adenomyosis (2,10). Tamura et al. established that the women with diffuse adenomyosis had an increased risk of second-trimester miscarriage, cervical incompetency, increased risk of preeclampsia, and uterine infection (10). Adenomyotic lesions may cause myometrial stiffness, chronic inflammation, altering endometrial function and receptivity.

These alterations impair foetal development and placental function, potentially increasing the risk of early pregnancy loss or spontaneous miscarriage (2–4,10,15,22). A 2017 case-control study conducted by Hashimoto et al. found that all 49 pregnant women diagnosed with adenomyosis had an increased risk of second- trimester miscarriage due to adenomyotic alterations of the endometrial function and receptivity (8). Tamura et al. linked miscarriages to increased myometrial stiffness and intrauterine pressure in patients with adenomyosis (10). When a significant portion of the placenta is in contact with adenomyotic lesions, there is an increased risk of reduced blood circulation within the intervillous space leading to foetal growth restrictions (23). Adenomyotic lesions may adversely affect placentation and spiral artery transformation, which can contribute to the pathogenesis of foetal growth restrictions (3–5,8,9). Preeclampsia, which involves arterial hypertension and proteinuria, is also associated with abnormal placentation and vascular function (2,14,16). Tsikouras et al. found that in preeclamptic women, a significant proportion of the spiral arteries are abnormal (due to the effect of adenomyosis), causing pathological placentation, with increased vascular resistance, activation of the coagulation mechanisms, and endothelial dysfunction (24). Adenomyosis may cause increased local inflammation and elevated prostaglandin levels (2,15,16). An ensuing inflammatory response and increased prostaglandin levels create an abnormal uterine environment, predisposing one to preterm labor and premature rupture of membranes (PPROM) before 37 weeks of gestation (16). Preterm labor involves regular uterine contractions that lead to cervical changes before 37 weeks of pregnancy. PPROM involves the rupture of the amniotic sac before labor begins, and before 37 weeks of pregnancy (1,2,15,16). In a case-control study involving a cohort of 2138 pregnant women, Juang et al. established that women with adenomyosis had increased instances of preterm delivery and preterm pre-labor rupture of membranes (25). These obstetric complications could be attributed to increased local inflammatory response and higher levels of prostaglandins in these women (25). The abnormal uterine environment in adenomyosis raises the risk of abnormal placental implantation (like placenta previa or placental abruption) which are associated with increased risks of preterm birth, haemorrhaging, and other adverse pregnancy outcomes (1,2,16,26). Orozco et al. analysed obstetric outcomes in 7,608 pregnant patients with adenomyosis and found that placental abruption occurred in 3.9% of the patients, implying that the risk of presenting abruption placentae increased by 19% in these patients compared to those without adenomyosis (3). Adenomyotic lesions disrupt normal uterine contractility, increasing risks of uterine atony and postpartum haemorrhage (10). The risk of post-partum complications is significantly high among women with adenomyosis. In a multicenter retrospective survey involving 272 pregnant women with adenomyosis from 65 facilities, four women reported to have experienced atonic bleeding, and one patient experienced a uterine rupture (10). Most studies have generally established that women with adenomyosis have an increased likelihood of experiencing spontaneous miscarriages, preterm labor and preterm delivery, PPROM, SGA, preeclampsia, atonic bleeding, and uterine rupture compared to those without adenomyosis. The risk of rupture seems to be related to myometrial stiffness, poor stretchability, and contractility (1–6,8– 13,15,16,18,20,22,25–28).

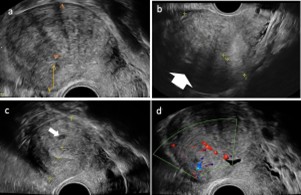

The Sonological Phenotypes of Adenomyosis

Adenomyosis disrupts the normal structure and function of the uterus. Specific phenotypes of adenomyosis include a bulky, globular uterus, asymmetrical myometrial thickening, myometrial cysts, irregular/interrupted junctional zone, hyperechoic islands, trans lesional vascularity and echogenic sub-endometrial lines and buds (21,29,30). The asymmetric or irregular thickening of the myometrium involves one wall (anterior, posterior, or lateral) appearing significantly thicker than the others. This asymmetrical thickening depicts areas with adenomyotic foci/infiltration. Myometrial cysts are circumscribed anechoic cystic areas seen within the myometrium, often corresponding to dilated adenomyotic glands (20,29). The junctional zone is a thin hypoechoic line that separates the endometrium from the outer myometrium (21). It appears thickened, interrupted, or ill-defined due to infiltration by adenomyotic lesions. Hyperechoic islands are regions of increased echogenicity in a linear or nodular pattern scattered within the myometrium (21). On Doppler imaging, trans lesional vascularity is seen as increased vascularity with prominent penetrating vessels running through the adenomyotic areas within the myometrium. Echogenic sub-endometrial lines and buds are fine echogenic linear bud-like projections and striations extending from the endometrium into the myometrial substance, highlighting infiltration by endometrial tissue into the myometrium (29) (Figure 2).

Adenomyosis Presentation in Pregnancy

Pregnancy brings significant changes in hormones. Hormonal changes, particularly those due to progesterone, stimulate decidualization in endometrial tissues and may also affect or involve ectopic tissues resulting from adenomyosis (31). Hormonal effects can cause changes in the imaging appearances of adenomyosis and may pose a diagnostic issue if adenomyosis mimics other types of uterine or placental abnormalities, including placenta accreta or gestational trophoblastic disease (31). An example of this is the thickening of adenomyosis with a cystic feature, which could be misinterpreted as trophoblastic tissue. This is most likely with cystic adenomyosis that may be surrounded by decidualized tissue and simulate an early gestational sac or intramural ectopic pregnancy (30). Focal adenomyosis may display irregular, poorly demarcated lesions within the myometrium, which may extend into or distort the placental region (31). These features can pose a challenge in separating the latter from placental anomalies. Diffuse adenomyosis may show thickened and heterogeneous myometrium that can change the shape and/or position of the gestational sac (31). Ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) will remain essential, particularly lower frequency transducers or non-contrast MRI that can more easily differentiate between placental and myometrial boundaries (31).

Mechanisms through which Adenomyosis causes Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes

Abnormal Placentation: Adenomyosis may affect placental development, potentially yielding adverse pregnancy outcomes. Junctional zone alterations in women with adenomyosis can affect the vascular resistance of junctional zone spiral arteries to decidualization, increasing the likelihood of insufficiently deep placentation (4). The restriction of physiological transformation of the spiral artery may cause miscarriage, and a lower level of hypoxia may cause foetal fatalities. During embryogenesis, trophoblastic cells invade the endometrium and the myometrial junctional zone to allow decidualization and vascular changes (10). Foetal growth issues occur when blood vessels do not undergo physiological change due to inadequate deep placentation (10). Poor formation of myometrial spiral artery might cause placental abruption by elevating the blood flow rate from the uterine artery (4). A dysfunctional junctional zone (usually > 7mm) is associated with implantation failure (1). Understanding of junctional zone abnormalities in adenomyosis may guide in ensuring targeted intervention to improve placentation.

Immunological changes:: Adenomyosis may alter immune profiles in the endometrium which can cause placental abnormalities (2,32). The eutopic endometrium in adenomyosis has abnormal immune cell types and inflammatory indicators, which contribute to implantation failure (32). Both innate and adaptive immune cells increase in the endometrium. These additional immune cells produce pro-inflammatory signals, resulting in an inflammatory environment within the uterus (2,32). Concurrently, adenomyosis patients have fewer uterine natural killer (uNK) cells in their endometrium, which play an important role in implantation and placentation (32,33). This uNK cell deficit is characterized by an increased expression of the inhibitory receptor CD94 on these cells, which inhibits their function. The immunological alterations, together with steroid hormone abnormalities such as progesterone resistance, reduce endometrial receptivity, which is necessary for optimal implantation and placental development (32). In essence, increased inflammatory cells and mediators, along with impaired uNK cell activity, create an unfriendly endometrial environment, preventing embryo implantation and placentation (32). This immunological dysregulation, defined by excessive inflammation but repressed uNK activity, interacts with progesterone resistance to raise the likelihood of unfavourable outcomes such as implantation failure, miscarriage, and placental abnormalities. in women with adenomyosis (32,33). Can these immune alterations in adenomyosis be modified through specific interventions to enhance endometrial receptivity?

Hyperinflammatory microenvironment:: Adenomyosis creates a hyperinflammatory microenvironment in the uterus (34), potentially causing immune responses within the uterus, which can impair normal placentation. Women with adenomyosis have increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and markers such as interleukin-1 (IL-1), IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) in the endometrium and myometrium (10,34). The inflammatory state in adenomyosis elevates the production of free radicals. This process causes oxidative stress and damages embryonic cells thus inhibiting normal embryo development and implantation process (4). Some studies have shown increased expression of prostaglandins, inflammatory mediators in the eutopic and ectopic endometrium of women with adenomyosis (10). Prostaglandins can induce uterine contractions and impede implantation (10). Adenomyosis lesions overexpress the enzyme cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), causing elevated prostaglandin production and propagating the inflammatory cycle (10). This persistent hyperinflammatory microenvironment hinders embryo implantation and normal placental development (10). Therefore, anti-inflammatory prophylaxis be explored to minimize oxidative stress and enhance normal placentation?

Myometrial wall Contractility:: Myometrial contractility is crucial in pregnancy. Adenomyotic lesions significantly alter myometrial contractility. Adenomyosis leads to increased uterine wall thickness, elevated intrauterine pressure, and abnormal uterine contractility (30). The increased wall thickness and distortion of the myometrium can cause stiffness and elevated intrauterine cavity pressures during pregnancy (10). This can contribute to pregnancy complications such as pre-term labor and birth. Adenomyosis also disrupts the normal make-up and function of the myometrial smooth muscle. This disruption causes dysregulated uterine contractility patterns. Abnormal and excessive uterine contractions can occur in late pregnancy (10).

Abnormal progesterone receptors:: Hormonal environment in the uterus is critical in maintaining pregnancy. Adenomyosis disrupts this hormonal environment. Adenomyosis characterizes an abnormal response to the hormone progesterone due to the reduced expression of progesterone receptors (PR) in the myometrium (26). Women with adenomyosis have lower levels of PR, hence a diminished response to circulating progesterone levels (35). This progesterone resistance leads to unopposed estrogenic effects, as the downregulation of PR causes a corresponding upregulation of estrogen receptors (ER) (35). The increased ER expression alters the expression profiles of cellular adhesion molecules like integrins and cadherins, which are crucial for embryo- endometrial interactions during implantation (35). Notably, the levels of integrin B-3 are low in adenomyosis, impairing embryo attachment and implantation (35). The progesterone resistance perpetuates the proliferative and inflammatory state in adenomyosis (35). Progesterone insensitivity, alongside excess estrogenic actions and inflammatory mediators can cause implantation failure, miscarriages, and placental abnormalities observed in pregnancies complicated by adenomyosis (35). Therefore, enhancing progesterone receptor sensitivity in women with adenomyosis may reduce implantation failure and improve pregnancy outcomes.

Chronic Impaired Inflammatory State of the Endometrium (CIISE): CIISE is an inflammatory endometrial disorder. Adenomyosis increases the risk of CIISE (19). Khan et al., asserts that CIISE is mostly asymptomatic and sometimes shows subtle symptoms such as pelvic discomfort, spotting, and leukorrhea (19). Some studies have linked CIISE to reproductive failures, including recurrent implantation failures post IVF-ET, repeated miscarriages, and mysterious infertility (19,36,37). The inflammatory state caused by CIISE delays the proper differentiation of the endometrium during the mid- secretory phase, which is vital for embryo implantation (19). CIISE downregulates the expression of genes associated with embryo receptivity and decidualization, creating a hostile environment that impairs embryo implantation (36,37). The plasma cells that accumulate in the endometria of women with CIISE produce excessive levels of mucosal antibodies, predominantly IgG2, which can directly interfere with the implantation processes (19). Therefore, targeting the inflammatory and immunological pathways in CIISE could enhance endometrial receptivity and reduce pregnancy complications due to adenomyosis.

Results and Findings

Different Treatment Approaches to Ensure Positive Pregnancy Outcomes: Since there is still no consensus on any specific approach to manage adenomyosis in pregnant women, can an appropriate treatment approach involve an attempt to address the mechanisms through which adenomyosis causes adverse pregnancy outcomes?

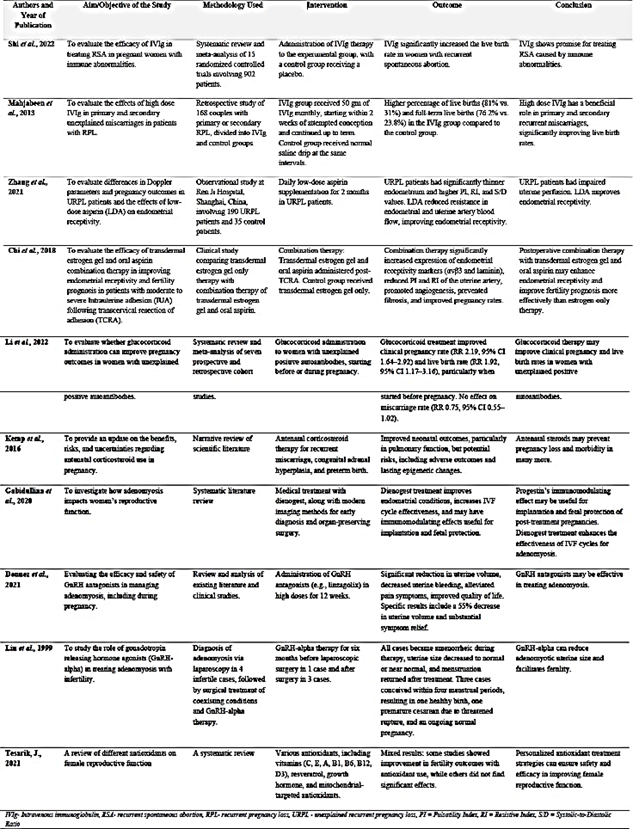

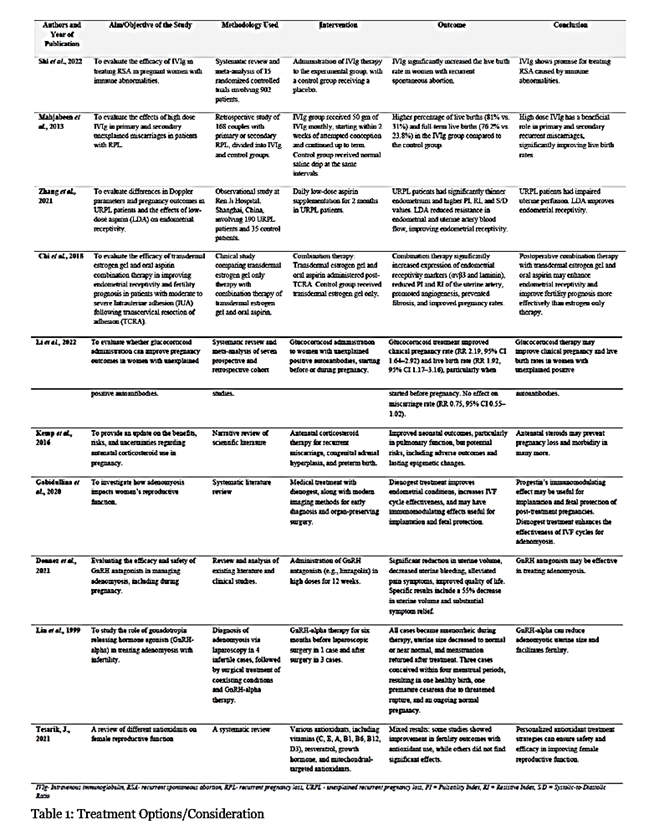

Table 1 summarizes several treatment approaches that can be used to ensure successful pregnancy outcomes. These studies look at different kinds of interventions aimed at minimizing complications during pregnancy. Interventions covered include intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) therapy, low-dose aspirin supplementation, corticosteroid administration, hormonal treatments such as progesterone and GnRH agonists, and combination therapies.

Discussion

Managing adenomyosis in pregnant women is a complex issue. It requires a holistic management that can address key issues on how the mechanisms in adenomyosis affects the uterus. Such mechanisms include abnormal placentation, immunological changes, hyperinflammatory microenvironment, contractility of the myometrial wall, abnormal receptors for progesterone, and chronic impaired inflammatory state of the endometrium). Proper management may include intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg), low-dose aspirin, corticosteroids, hormonal therapy such as progesterone and GnRH agonists, or combination therapies. IVIg may modulate the maternal immune response by supplying natural antibodies, regulating cytokines, and inducing foetal-maternal tolerance once the pregnancy is established. After pregnancy confirmation, a regimen of 500 mg/kg over 5 days per month would provide treatment until 34 weeks’ gestation (39). High-dose IVIg is also feasible, which would be 20 grams administered daily for 5 consecutive days during the early stages of gestation (40). Low- dose aspirin therapy can improve endometrial receptivity and reduce pregnancy complications (16,41,42). A dosage of 50 to 75 mg daily, administered from 12 to 36 weeks of gestation, is recommended. Aspirin has anti-inflammatory effects and prevention of platelet aggregation (16,41,42). This improves uterine blood flow, enhances endometrial growth, and reduce the risk of preeclampsia and other placental-mediated complications. The combination of aspirin with other therapies, such as transdermal estrogen gel, may improve endometrial receptivity and pregnancy outcomes (16,41,42). Progesterone supplementation (like dienogest) may enhance implantation and foetal protection (9,43). Nevertheless, the optimal timing, dosage, and duration of progesterone therapy in adenomyosis-complicated pregnancies require further research. Gonadotropin- releasing hormone agonists (GnRH-a) can be potential preconception treatment for adenomyosis. GnRH-a therapy reduces the size of adenomyotic lesions and creates a more favourable uterine environment for implantation. The regimen may involve administering GnRH-a for 3 months prior to attempting conception to improves implantation rates (35,44). GnRH-a therapy must be discontinued before conception due to its potential teratogenic effects. The use of corticosteroids (such as prednisolone) is still undergoing research. Low-dose prednisolone (5-10 mg daily) started before conception or in early pregnancy may help correct immunological imbalances associated with recurrent miscarriage (45). However, corticosteroids may increase the likelihood of gestational diabetes and preterm birth (46). Therefore, the optimal timing and duration of corticosteroid therapy in adenomyosis require further investigation. Adenomyosis can impair mitochondrial activity in uterus cells (47). Antioxidants such as CoQ10 reduce oxidative stress (48) and may also be administered to improve mitochondrial function. CoQ10 has been shown to have anti-inflammatory properties that could potentially reduce inflammation associated with adenomyosis (48). Further research into the dosage, timing, and combination of these interventions in adenomyosis- complicated pregnancies is crucial. The exploration could pave way for personalized treatment strategies to enhance pregnancy outcomes.

Conclusion

Adenomyosis significantly increase the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes, which include miscarriage, preterm birth, various hypertensive disorders, placental abnormalities, and postpartum complications. Such outcomes arise due to the complex adenomyosis- associated mechanisms, such as immune dysregulation, hyperinflammatory milieu, impaired placentation, myometrial dysfunction, progesterone resistance, and chronic impaired inflammatory state of the Endometrium (CIISE) (49). Managing pregnancy with adenomyosis in women necessitates an integrative approach that considers these mechanisms. IVIg has good potential for improving pregnancy outcomes through modulation of the maternal immune system and enhanced foetal-maternal tolerance. Low-dose aspirin therapy may foster endometrial receptivity and vascularization and perhaps lower the incidence of a multitude of such problems. Proper utilization of corticosteroids before conception or in early pregnancy may help correct immunological imbalances linked with recurrent miscarriage, but the risks and uncertainty around adenomyosis require further research. Dienogest-progesterone supplementation prior to pregnancy may offer a suitable uterine environment for implantation and foetal development by acting as an anti-inflammatory and immunomodulator. Furthermore, antioxidants such as CoQ10 may reduce oxidative stress and inflammation associated with adenomyosis, hence improving pregnancy outcomes. While no single treatment is 100% effective, a multimodal strategy customized to the individual patient’s clinical presentation and risk variables may provide the highest chance of a favourable pregnancy result. Thorough investigation is imperative to develop and optimize current care techniques, ensuring that women with adenomyosis can have safe pregnancies with reduced the risk of adverse outcomes.

Recommendation

Administering GnRH-a for three months prior to pregnancy (either natural or IVF attempts) to improve implantation and reduce the risk of miscarriages is recommended. This will suppress estrogen production, and allow a temporary reduction in the size and activity of adenomyotic lesions. By creating a more favourable uterine environment, GnRH-a therapy may improve implantation rates and reduce the risk of early miscarriage. The improved uterine environment results from decreased inflammation, reduced myometrial hyperactivity and enhanced endometrial receptivity.

References

Figure 1: The PRISMA protocol for selecting the relevant studies utilized in the review

Figure 2: 2-D sonographic imaging of a non-gravid uterus in a longitudinal section highlighting typical phenotypes of adenomyosis. (a) See the globular shape with an asymmetrical myometrial wall-thickening (posterior thicker than anterior – orange arrows), the heterogeneous myometrium with hyperechoic regions, and hypoechoic striations. (b) asymmetrical myometrial wall-thickening (anterior thicker than posterior), the heterogeneous myometrium with fan-shaped shadowing (white arrow). Note the ill- indistinct endometrial-myometrial border (c) A solitary myometrial cyst on the posterior wall (white arrow). (d) Few diffuse vessels (increased vascularity) can be seen on colour Doppler

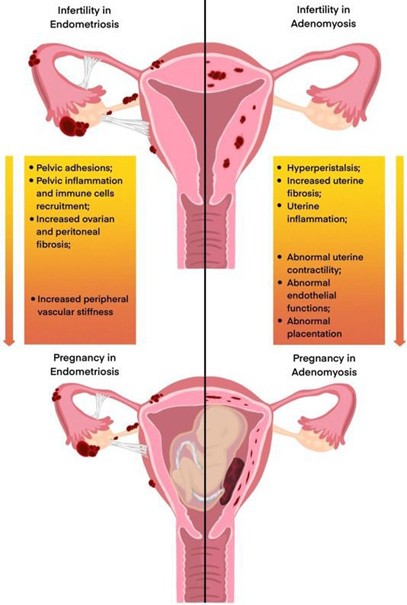

Figure 3: Mechanisms of adverse reproductive and pregnancy outcomes in women with pelvic endometriosis and adenomyosis. Used with permission from “Association of endometriosis and adenomyosis with pregnancy and infertility.” (38) DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2023.03.018 License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Table 1: Treatment Options/Consideration

Table 2: Treatment Options/Consideration